If you’ve ever been detained by law enforcement officers, you may have wondered what your rights are. The truth is that there are a lot of misconceptions about when and how the police detain someone.

And sometimes, police make mistakes during detentions that lead to a violation of civil rights. In this article, we’ll answer the questions: when can police detain you, what are your rights, and what is the difference between being detained and arrested?

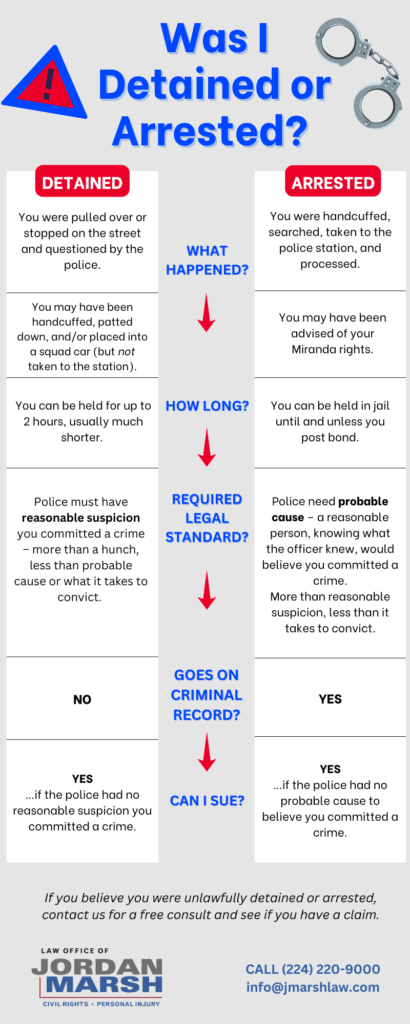

When a police officer detains you, you are held in police custody for a short period of time. Under certain circumstances, police officers can temporarily detain a suspect while the officer conducts a brief investigation to determine if the suspect is involved in criminal activity. This is called an investigative detention.

During an investigative detention, the suspect is not free to leave, may be handcuffed for officer safety, and may even be frisked (briefly searched) for weapons. This is often referred to as a “Terry stop,” named for the U.S. Supreme Court decision, Terry v. Ohio, that first approved the concept of investigatory detentions.

Being detained doesn’t usually mean that police can search your home or property, but some exceptions may allow police to search your stuff. You may be asked to come to the police station after being detained.

An investigative detention may last anywhere from a few seconds to more than an hour, though there is no absolute time limit for a detention.

However, it “must be temporary and last no longer than is necessary to effectuate the purpose of the stop…” United States v. Segoviano (N.D. Ill. 2019). In other words, the duration of a detention must be reasonably related to the officers’ investigation. Rarely are detentions more than an hour.

The Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution prohibits unreasonable searches and seizures. Arrests and detentions are considered “seizures” under the law. Traditionally, courts held that any seizure required probable cause to believe that the person being seized had committed a crime.

However, in 1968, the U.S. Supreme Court created an exception to the probable cause rule. It held that the police could temporarily detain suspects as long as they had reasonable suspicion (a lower standard than probable cause) to believe the person being detained was involved in criminal conduct.

Still, the police can detain you only if they meet constitutionally mandated standards. Probable cause and reasonable suspicion are the two key standards that can lead to detention and possibly an arrest.

In order to justify a detention, an officer must be able to articulate specific facts that lead to a reasonable suspicion that the suspect is involved in criminal activity. A detention is not an arrest, but reasonable suspicion requires less evidence than probable cause.

To briefly detain a citizen, an officer must have reasonable suspicion that the person being detained has been involved in criminal conduct.

The Reasonable Suspicion standard requires less evidence of criminal conduct than the standard of Probable Cause. However, it must still be based on specific facts that the officer can articulate. It must be more than a hunch.

This standard, like probable cause, depends on the circumstances of each specific situation. But, first, the officer has to be able to identify specific facts justifying their suspicion that the suspect was involved in criminal activity.

Without those specific facts, the suspicion is unreasonable, and the person detained may have a civil claim for unlawful detention.

A detention can lead to an arrest if the officer finds sufficient evidence during a detention to provide probable cause to make an arrest.

While detained, the police officer might find some other evidence giving them probable cause to arrest you. Remember, this does not necessarily mean that you are guilty – it simply means that the officer thinks there is enough cause to arrest you.

Reasonable suspicion is not a sufficient basis to arrest someone. An officer must have probable cause to make an arrest.

Everyone has a constitutional right against unreasonable searches and seizures. An arrest without probable cause is a violation of that right.

Unlike detention, an arrest involves taking a suspect into police custody, where the suspect is not free to leave after a period of time. In addition, an arrest requires probable cause, which is more difficult to prove than reasonable suspicion.

To arrest a suspect, a police officer must have probable cause. Probable cause exists when facts and circumstances within the police officer’s knowledge would lead a reasonable person to believe that the suspect is involved in criminal activity.

Probable cause can’t be established merely by suspicion. It requires more proof than a hunch but less than it takes to convict a defendant in court. An officer must be able to articulate specific facts that led him to believe the suspect had committed or was committing a crime.

Officers can rely on hearsay to establish probable cause. In other words, officers can rely on what a third person tells them. So if someone flags down an officer, points to you, and tells the officer you stole her purse, that may be sufficient to establish probable cause to arrest you.

But the statement must still be reasonable. For example, if a woman flags down an officer, points at you, and says that you stole her purse and that you shot President Kennedy, that would make her identification less reasonable. It would likely undermine any probable cause.

The statement must also be specific. For example, if the victim tells the officer only that a Black male stole her purse, the officer cannot arrest you simply because you are a Black male. That is not a reasonable basis to establish probable cause.

The probable cause standard must be more than suspicion and more than a hunch but can be less than the legal standard to convict – by which a judge or a jury must be convinced of a defendant’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. So the fact that a criminal defendant was later acquitted does not necessarily mean that his arrest lacked probable cause.

In other words, an officer may have probable cause to arrest even if the suspect turns out to be innocent or is found not guilty after a trial. But it is always worth speaking to a qualified civil rights attorney to see if you have a false arrest case.

Whether an officer has reasonable suspicion or probable cause determines their power to detain or arrest you.

If you’re arrested or detained, remember that your number one priority is your physical safety and safe release. Even if you believe your arrest is unlawful, don’t resist arrest.

Just because a police officer questions you doesn’t mean you have to respond. Tell the police officer your name, address, and birthday if requested, and state clearly that you are invoking your fifth amendment right to remain silent.

If you believe you’ve been a victim of false arrest or excessive force, document what happened and contact a lawyer as soon as possible. Even if you don’t believe your rights have been violated, you still have a right to legal representation by a criminal defense attorney.

If you were held for a brief time to be questioned before being released, you were detained. You may not be free to leave during the duration of the detention, but you also weren’t under arrest. A common example is when a driver is pulled over for a traffic violation, or a pedestrian is stopped and briefly interrogated.

When an officer prolongs the detention beyond what is considered “brief and cursory” while restraining you in some way, then an actual arrest has occurred (though it may not be an official arrest). During an arrest, you are not free to leave as you please. You may experience wrongful detention if the police officer doesn’t have enough reasonable suspicion to hold you.

The police can only arrest you when they have probable cause to do so. Reasonable suspicion is enough to justify detaining you but not enough to arrest you.

Whether an officer can detain or arrest you depends entirely on the situation. But in any case, the officer must meet constitutional standards before denying your liberty. Otherwise, you’ve been the victim of unlawful detention or a false arrest.

If you believe that you or someone you know has been the victim of a wrongful detention or a false arrest, contact Chicago civil rights attorney Jordan Marsh for a free consultation.

The information provided on this website does not, and is not intended to,

constitute legal advice; instead, all information, content, and materials available on this site are for general informational purposes only. Use of and access to this website or any of the links contained within the site do not create an attorney-client relationship between you and our office.